- HOME

- ABOUT

- ORAL HISTORIES

- Bill Holbert

- Bill Russell

- Charlene Wooten Pace

- Charlie Fears

- Donna “Donnie” Morgan Pace

- Faye Russell Chandler

- George Jones

- Henry Twiggs

- J.D. Gilbert & Lula Staton

- John Rhodes

- Kathleen Garren Stephenson Jelley

- Martha Coates Ashley

- Martha Stoney Anderson

- Mildred Thompson Skelton

- Ruth Pace Lawter and Betty Jo Pace Thompson

- Pearlie Mae Suber Harris

- SALUDA HISTORIC DEPOT

- COON DOG DAY & OTHER EVENTS

- HISTORIC DISTRICT

- HISTORIC INNS & HOMES

- OLD PHOTOGRAPHS

- SALUDA HISTORY

- SALUDA PEOPLE

- SCRAPBOOK AND NEWS

- THE RAILROAD

- TOUR OF HISTORIC HOMES

- VINTAGE POSTCARDS

- VISIT SALUDA

Historic Saluda Historic Saluda North Carolina Established in 1881

Historic Saluda | Memories, Places, and People That Make Saluda NC an Enchanted Place to Be

HISTORIC INNS & HOMES

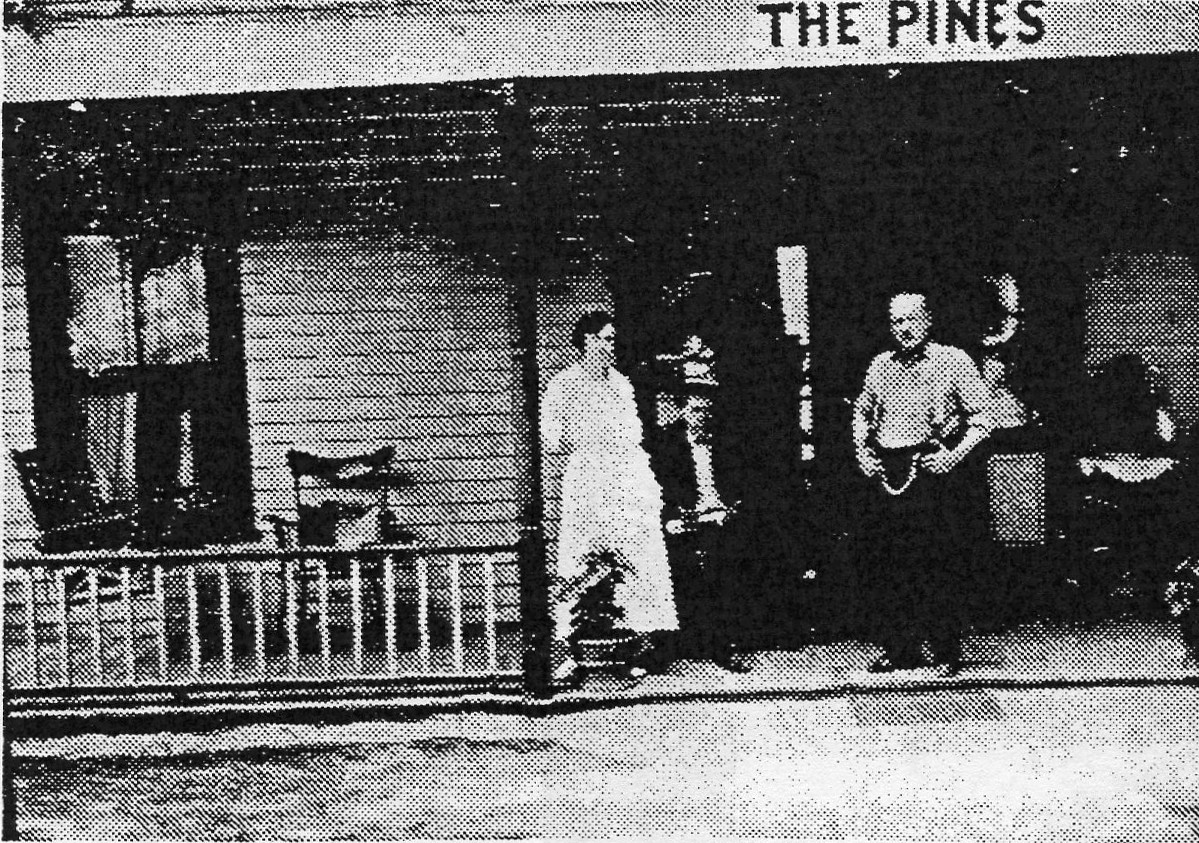

The earliest boarding house in Saluda was the Ransom Pace House, which was established before Saluda was even a town, back in the days of the drovers. Located on the Howard Gap Road, it became a stagecoach stop and offered eloquent flouishes. (See the dining room table in the photo to the right.) The Pace House is seen in the photo to the left, with the owner/proprietor Ransom Woodruff Pace in the foreground, to the left. His wife Emily is diagonally across from him standing on the porch. You can hear Ransom Woodruff Pace’s granddaughter Kathleen Garren Stephenson Jelley talk about her memories of the Pace House here.

The earliest boarding house in Saluda was the Ransom Pace House, which was established before Saluda was even a town, back in the days of the drovers. Located on the Howard Gap Road, it became a stagecoach stop and offered eloquent flouishes. (See the dining room table in the photo to the right.) The Pace House is seen in the photo to the left, with the owner/proprietor Ransom Woodruff Pace in the foreground, to the left. His wife Emily is diagonally across from him standing on the porch. You can hear Ransom Woodruff Pace’s granddaughter Kathleen Garren Stephenson Jelley talk about her memories of the Pace House here.`

`

`

`

`

`

`

`

`

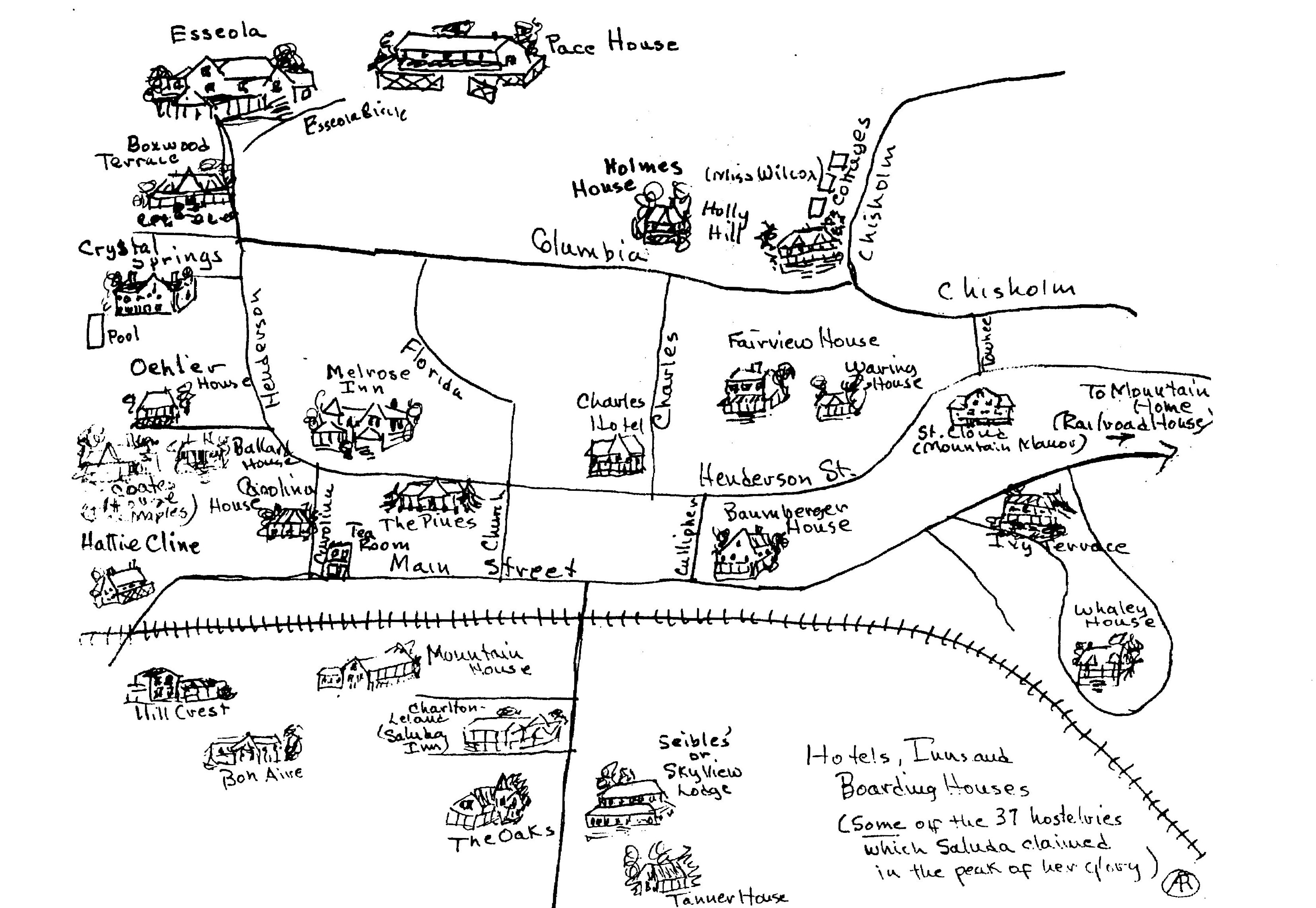

The coming of the railroad would seem to explain the existence of Saluda. However, fear also had its place of importance. For it could be said that Saluda was spawned in the malarial swamps of South Carolina as much as it was forged by the men who built the railroads. The people of the 19th century believed that the marshy southern climate was very unhealthy, causing a range of disorders brewed in the “miasma” of the swamps. To escape that curse, they went far afield of the rice and indigo plantations to resorts along the seacoasts or inland to drier areas and to the “healthy” higher elevations of the mountains. As early as 1836 Flat Rock, just six miles from Saluda, had become one of the major centers for summer migrations by the South Carolina planter aristocracy. But Saluda was to remain untapped as a resort area until well after the Civil War decimated that class, causing Flat Rock’s decline. Saluda’s heyday was from 1880-1930 when the small town sported dozens of inns, hotels and boarding houses.

The coming of the railroad would seem to explain the existence of Saluda. However, fear also had its place of importance. For it could be said that Saluda was spawned in the malarial swamps of South Carolina as much as it was forged by the men who built the railroads. The people of the 19th century believed that the marshy southern climate was very unhealthy, causing a range of disorders brewed in the “miasma” of the swamps. To escape that curse, they went far afield of the rice and indigo plantations to resorts along the seacoasts or inland to drier areas and to the “healthy” higher elevations of the mountains. As early as 1836 Flat Rock, just six miles from Saluda, had become one of the major centers for summer migrations by the South Carolina planter aristocracy. But Saluda was to remain untapped as a resort area until well after the Civil War decimated that class, causing Flat Rock’s decline. Saluda’s heyday was from 1880-1930 when the small town sported dozens of inns, hotels and boarding houses.

The farsighted soul who undertook the erection of the first hostelry was the very man in charge of the railroad line’s construction- Col. Andrew Tanner. As overseer of the chain gangs of convicts who worked the road, he helped open the area and would serve later as Saluda’s first Mayor in 1882. The Colonel, more than any of the other hotel owners who came after him, understood the benefits of providing entertainment for his guests. To that end, by the mid 1880′s he had made extensive improvements to his facility on Greenville Street by adding a billiard room, pool tables and a bowling alley.

At first, the exposure that Saluda received from travelers was accidental. The railroad simply stopped once the line topped the Saluda Grade. To continue their journey, travelers to mountain resorts farther on had to board stages and other overland conveyances. So it was no mystery why Saluda quickly came to notice. Also, the interruption was long enough for a small mercantile community to get established based on the disembarking passengers as well as the families who moved to the vicinity to work for the railroad.

At first, the exposure that Saluda received from travelers was accidental. The railroad simply stopped once the line topped the Saluda Grade. To continue their journey, travelers to mountain resorts farther on had to board stages and other overland conveyances. So it was no mystery why Saluda quickly came to notice. Also, the interruption was long enough for a small mercantile community to get established based on the disembarking passengers as well as the families who moved to the vicinity to work for the railroad.

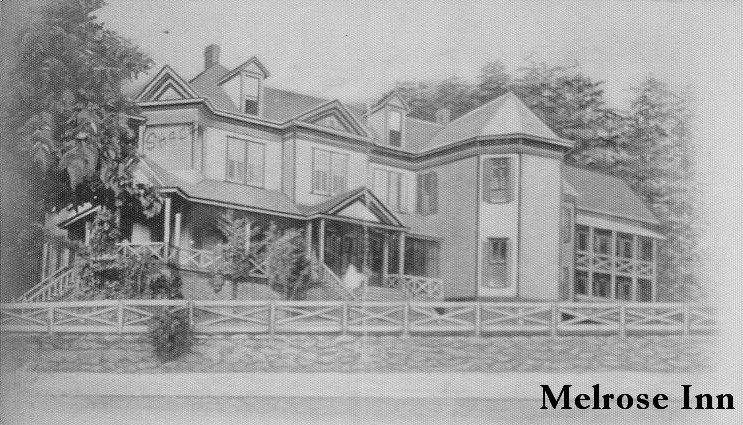

As the tourist industry grew, the Melrose Inn on Henderson Street was established in 1893 by two sisters from Charleston, Emma and Agnes Heriot. The large inn was designed to take in a more permanent guest than the other hotel, though it would not until the early 1900′s supplant the Mountain House in popularity.

To accommodate the tourist who wished to stay for extended periods, boarding houses also got off to an early beginning in Saluda. By the year 1900, at least two were in operation—Bon Air on Smith Hill established in June 1898 near the Mountain House and another summer boarding house run by Emmy Holmes in what would become Columbia Heights. The Holmes boarding house was established sometime in the early to mid 1890′s by the best estimates. Both of the two known boarding houses prior to 1900 had a fairly constant clientele with the guests from one season returning the following year for the most part—again beginning a trend for the years to come.

A souvenir booklet published on Saluda around 1900 contains a list of about a dozen names of proprietors of summer cottages and available rooms for rent. The proprietors were mostly women from Charleston and Columbia.

A souvenir booklet published on Saluda around 1900 contains a list of about a dozen names of proprietors of summer cottages and available rooms for rent. The proprietors were mostly women from Charleston and Columbia.

What designated an establishment as an inn, hotel or a boarding house depended a great deal on the sort of clientele sought and services offered. While all three offered bed and board, the hotels primarily housed a more transient group who generally stayed for shorter visits than those who took up residence in the other two. A boarding house, on the other hand, had a fairly permanent list of guests who generally stayed for the entire season and returned year after year. An inn was a sort of hybrid of the two fixed to accommodate either group. They were generally as large as the hotels, and like both the boarding houses and hotels were wrapped by huge porches filled with rocking chairs and sofas.

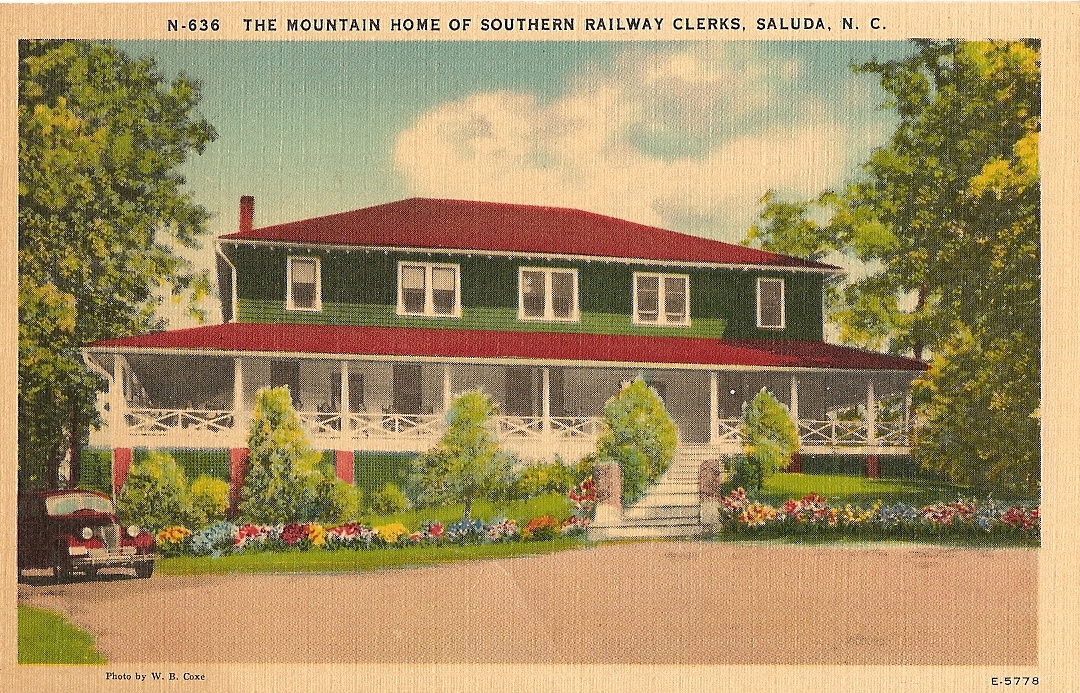

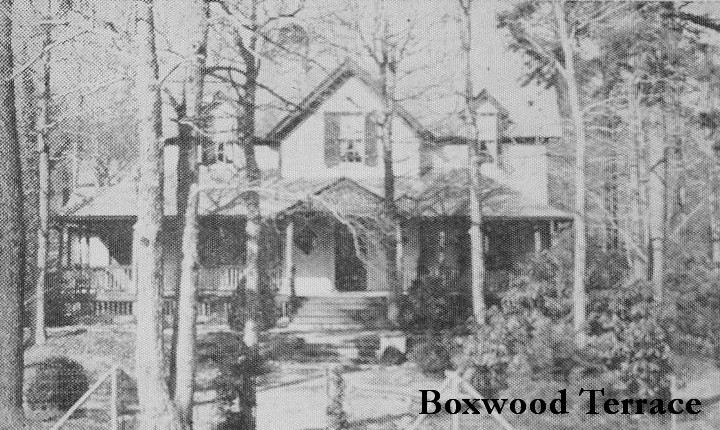

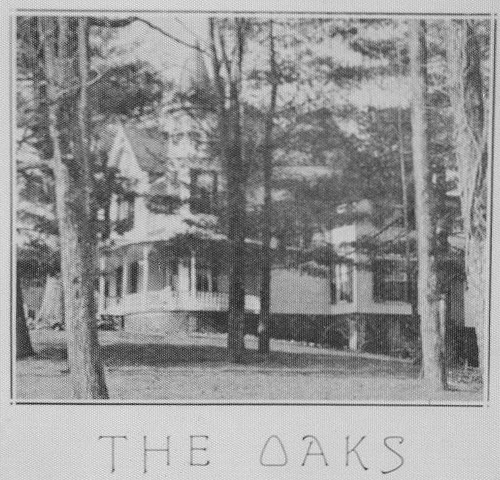

By 1910 there were seven operating inns and hotels: Mountain House, Melrose Inn, Fairview, Esseola, Hill Crest, The Charles and Crystal Springs followed shortly by the St. Cloud and Charleton-Leland, not to mention the multitude of the more important boarding establishments like The Oaks, the Sieble House on the western side of the city to the eastern half’s Ransom Pace House, Holly Hill, The Pines, Mountain Home (the Railroad Clerks’ house), The Clergy Houses (for Episcopal ministers), The Oehler Home, and later Ivy Terrace and Boxwood Terrace.

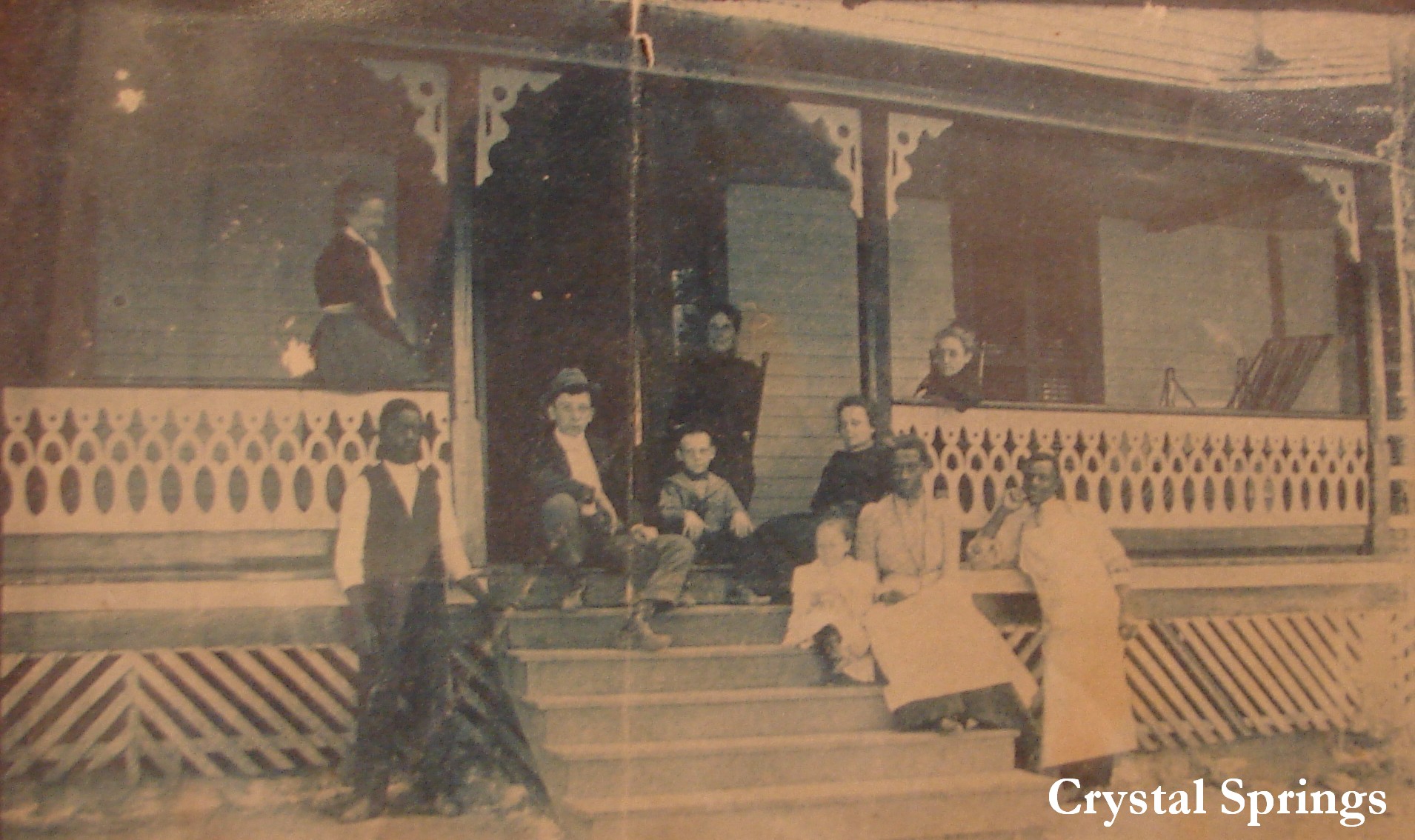

In the year 1901 alone, at least three- Crystal Springs, Fairview and the Esseola- were added to the ensemble. Crystal Springs was the brainchild of Charles Estes, a rich mill owner from Augusta, Georgia who fell in love with Saluda while staying at the Melrose Inn in 1899. As the site for his new inn he chose Henderson Street, which, along with Greenville Street, became a favorite avenue for the buildings. An additional bonus to the location was its spring, one of three that fed the creek that flowed along Main Street and ultimately formed the headwaters of the Pacolet River. Estes realized the clear cool waters could be turned to his advantage to provide running water for both his and the Melrose Inn, the first to have the amenity in Saluda. Using a ram near the source of the spring, the water welled up into the mechanism and once it reached a certain pressure was released in a gush of water into the crude wooden lines directly feeding the Crystal Springs and the water tower of the Melrose Inn. Later when water became generally available through a city-wide system fed by the reservoir at the top of Greenville Street, Estes dammed the spring for a swimming pool.

In the year 1901 alone, at least three- Crystal Springs, Fairview and the Esseola- were added to the ensemble. Crystal Springs was the brainchild of Charles Estes, a rich mill owner from Augusta, Georgia who fell in love with Saluda while staying at the Melrose Inn in 1899. As the site for his new inn he chose Henderson Street, which, along with Greenville Street, became a favorite avenue for the buildings. An additional bonus to the location was its spring, one of three that fed the creek that flowed along Main Street and ultimately formed the headwaters of the Pacolet River. Estes realized the clear cool waters could be turned to his advantage to provide running water for both his and the Melrose Inn, the first to have the amenity in Saluda. Using a ram near the source of the spring, the water welled up into the mechanism and once it reached a certain pressure was released in a gush of water into the crude wooden lines directly feeding the Crystal Springs and the water tower of the Melrose Inn. Later when water became generally available through a city-wide system fed by the reservoir at the top of Greenville Street, Estes dammed the spring for a swimming pool.

The two other inns that started during that year, the Esseola on the far end of Henderson Street and the Fairview House off Charles Street, prospered longer than Crystal Springs under their respective owners Mrs. Julia K. Campbell and Annie Locke. Mrs. Locke, later teaming with Rosa Box, formed the famous Locke-Box combination both in their summer inn in Saluda and in their winter boarding house, Tryon Lodge on Melrose Street in Tryon.

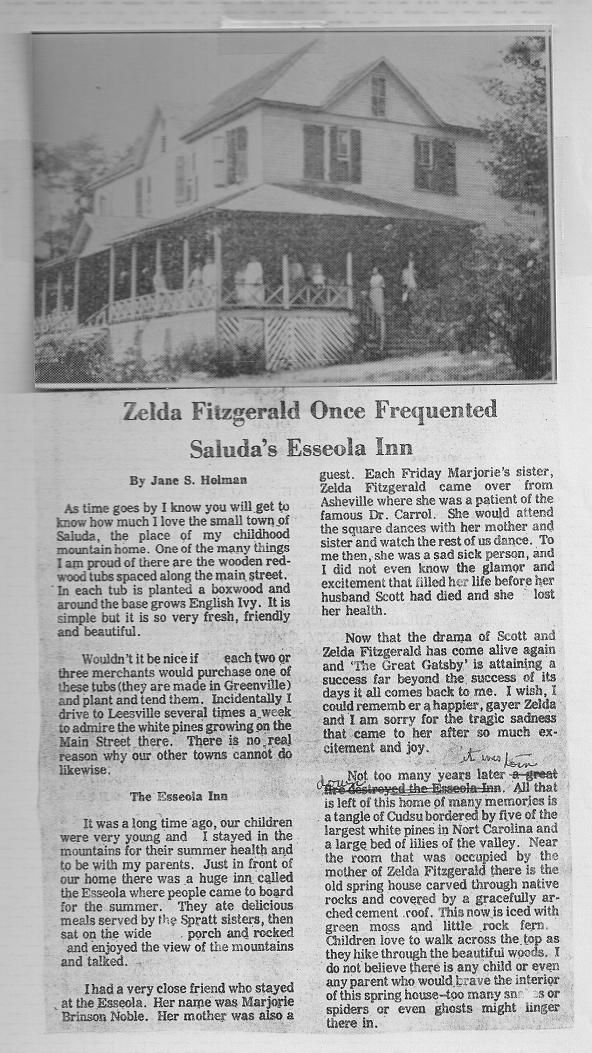

The earliest summer visitors to Saluda did not fall into the rich and famous category, except for the notable exception of the then unknown authoress Zelda Fitzgerald, wife of F. Scott Fitzgerald, who stayed for a while at the Esseola. (Zelda had stayed at Esseola as a child with her parents, Judge and Mrs. Sayre of Montgomery, Alabama, and, later, when she was a patient at Highland Hospital in Asheville, came to stay with her mother at Esseola.) Mostly the “summer people” were drawn from the professional class of Columbia and Charleston and brought their families to Saluda to escape the heat and pestilence that festered in the Lowlands. However, as the men still had to work regularly, most spent only the weekends, starting out from Columbia on the train Friday afternoons and leaving Saluda late Sunday or early Monday morning.

The earliest summer visitors to Saluda did not fall into the rich and famous category, except for the notable exception of the then unknown authoress Zelda Fitzgerald, wife of F. Scott Fitzgerald, who stayed for a while at the Esseola. (Zelda had stayed at Esseola as a child with her parents, Judge and Mrs. Sayre of Montgomery, Alabama, and, later, when she was a patient at Highland Hospital in Asheville, came to stay with her mother at Esseola.) Mostly the “summer people” were drawn from the professional class of Columbia and Charleston and brought their families to Saluda to escape the heat and pestilence that festered in the Lowlands. However, as the men still had to work regularly, most spent only the weekends, starting out from Columbia on the train Friday afternoons and leaving Saluda late Sunday or early Monday morning.

Boarding houses, too, started to spring up just after the turn of the century. Some like the Ransom Pace home, where the Saluda Nursing Home now stands, were homes that were converted to boarding houses as the summer crowds swelled. Holly Hill on Columbia Heights was also a private home built in the 1890′s that Lilian Wilcox saw fit to turn into a respectable summer hotel for boarders. During the early 1900′s one of the last great hotels was also constructed, the Charles, on Henderson Street across from the Episcopal Church of the Transfiguration. Though little is known about the ownership, it did provide a place for community dances  and teas after Tanner’s Mountain House was eclipsed by the Melrose Inn. As one would suspect, the lure of running water at the Melrose proved too much for the stately old hotel which by this time had begun to show the effects of age.

and teas after Tanner’s Mountain House was eclipsed by the Melrose Inn. As one would suspect, the lure of running water at the Melrose proved too much for the stately old hotel which by this time had begun to show the effects of age.

Of the three new inns, however, it was the Fairview House that proved most successful and survived the collapse of the tourist trade in the late 1920′s, possibly due to its low rates and the fine board it offered its guests.

Besides the inns and hotels mentioned, other numerous boarding houses made their appearance just after the turn of the century. Behind the Episcopal Church, Anne Waring set up her large home and the Carolina Inn, which was razed in the late I960′s, got started in what is now the parking lot of Saluda First Baptist Church.

The Oaks, on Greenville, was erected by the Lane family in 1908, followed soon after by the last of the great inns built in Saluda, the Charlton Leland just below it in 1914.

In 1928, Ryder Hall of the Saluda Seminary, built in 1909, was converted into the St. Cloud Hotel under the direction of Alice Fulton who had been in charge of Crystal Springs. “Fully”, a short stocky woman of a reportedly gregarious nature, was a professional innkeeper in the resort community. Later she would direct The Oaks until her retirement.

Railroad men had their own preferences as to boarding houses, the most popular of record being The Pines on Henderson Street next door to the Crystal Springs. (The rank and file workers, who could not afford The Pines, stayed at Hattie Cline’s close to the depot on the curve of Main Street.) However, before The Pines made its debut in the late 1910′s the mysterious Ballard House near the end of Poplar Street seems to have been the popular choice early in the century. However, it, like the Charles, must have disappeared rather quickly. Much later in the late 1920′s Southern Railway established the Clerks’ Mountain Home as a vacation spot for the Brotherhood of Railway Clerks.

Among other notable boarding houses that emerged after the turn of the century were the Oehler boarding house on Gaffney, Breeze Point on Coates Street, the Seibles boarding house on Greenville, which was rebuilt in the 30′s as Sky View Lodge by E.K. De Loach, and was one of the last of the inns to close.

Among other notable boarding houses that emerged after the turn of the century were the Oehler boarding house on Gaffney, Breeze Point on Coates Street, the Seibles boarding house on Greenville, which was rebuilt in the 30′s as Sky View Lodge by E.K. De Loach, and was one of the last of the inns to close.

The first all-weather road reached the town in 1928, making Saluda more accessible by auto; however, it also made points farther inland, in even higher elevations, and the newer resort areas with golf courses more accessible to the increasingly activity-minded tourists. Where once a family might spend months at an inn or boarding house, soon that was cut to weeks, and later days, except for those who owned homes in the area. Coupled with the swift advent of the Great Depression in October of 1929, it was enough to cripple the town for decades to come.

However, while many of the larger inns and boarding houses folded, there were some that survived the storm though at a much reduced state. Notably the larger establishments like the Charlton Leland, the Esseola, and the Fairview continued operations as well as the smaller boarding homes of The Oaks and The Pines.

Joining their ranks, in fact, to take up some of the trade left in the wake of the collapse of such establishments as the Crystal Springs, Melrose Inn, the St. Cloud, and the Charles Hotel, Boxwood Terrace under Mrs. Wendell Moore, Sr., and L.L. Clippard’s Ivy Terrace both opened their doors to summer boarders in the mid 1930s. Both had previously been private homes.

None, however, survived the further collapse of the tourist industry brought on by World War II. By the 1950s, only the railroad-subsidized Clerks’ Mountain Home survived. Its demise in the early 1960′s was brought on more by the social pressure of integration than the financial plight associated with the others.

None, however, survived the further collapse of the tourist industry brought on by World War II. By the 1950s, only the railroad-subsidized Clerks’ Mountain Home survived. Its demise in the early 1960′s was brought on more by the social pressure of integration than the financial plight associated with the others.

Time was not kind to many of the structures that were too large and unwieldy to be converted into private homes, unlike Boxwood Terrace, Crystal Springs, The Pines and Ivy Terrace that were small enough to comfortably make the adjustment.

Some burned immediately following the beginning of the Great Depression, such as The Charles, Melrose Inn and the Oehler House. Though there are some who believe that many of the fires were set for the insurance money, such cannot be substantiated. It may be suspicious that so many burned down within a short time, causing the insurance companies to raise a fuss. However, at the time, the clapboard structures were old and fire-prone with years of polishing the wooden floors with flammable oils. Combined with such possible factors as dry rot within the walls, it is not hard to believe that most were simply accidents.

Others, though, had a less dramatic exit, slowly being allowed to deteriorate in an abandoned state. Such was the condition of the Esseola, Warings’ boarding house, the Carolina Inn, the Sky View and Hill Crest before their demolition.

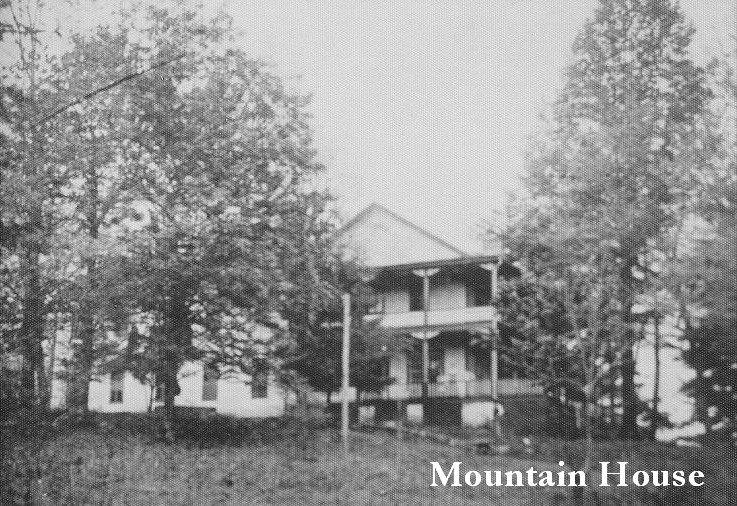

The Night “Mountain House” Burned Down

Mountain House was one of the first hotels in Saluda and was built by Andrew Tanner, a railroad contractor and the first mayor of the town. One snowy night in the 1920s, the building burned to the ground.

Mountain House was one of the first hotels in Saluda and was built by Andrew Tanner, a railroad contractor and the first mayor of the town. One snowy night in the 1920s, the building burned to the ground.

Reverend William “Bill” Ed Andrews, who spent most of his adult life as a missionary in Brazil, lived in Saluda for a few years when he was a child. He was one of eight children of Robert Franklin Andrews and Susie Meaders Andrews, who lived on Andrews Street.

Bill Andrews witnessed the burning of Mountain House, and he tells the story in this recording made shortly before his death in 2002:

(This recording was graciously donated to the city of Saluda by the Andrews family.)