- HOME

- ABOUT

- ORAL HISTORIES

- Bill Holbert

- Bill Russell

- Charlene Wooten Pace

- Charlie Fears

- Donna “Donnie” Morgan Pace

- Faye Russell Chandler

- George Jones

- Henry Twiggs

- J.D. Gilbert & Lula Staton

- John Rhodes

- Kathleen Garren Stephenson Jelley

- Martha Coates Ashley

- Martha Stoney Anderson

- Mildred Thompson Skelton

- Ruth Pace Lawter and Betty Jo Pace Thompson

- Pearlie Mae Suber Harris

- SALUDA HISTORIC DEPOT

- COON DOG DAY & OTHER EVENTS

- HISTORIC DISTRICT

- HISTORIC INNS & HOMES

- OLD PHOTOGRAPHS

- SALUDA HISTORY

- SALUDA PEOPLE

- SCRAPBOOK AND NEWS

- THE RAILROAD

- TOUR OF HISTORIC HOMES

- VINTAGE POSTCARDS

- VISIT SALUDA

Historic Saluda Historic Saluda North Carolina Established in 1881

Historic Saluda | Memories, Places, and People That Make Saluda NC an Enchanted Place to Be

SALUDA PEOPLE

Pat Hingle is one of the most famous of former Saluda residents. He was the grandson of Mr. and Mrs. E.M. Patterson of Saluda, and he and his mother moved to town when his parents divorced. Pat’s grandfather was engineer on the helper engines up the Saluda Grade for 40 years. Pat’s acting career began at Saluda School, where he had a part in a school play. He went on to appear on Broadway in Cat on a Hot Tin Roof, on TV in Gunsmoke, The Andy Griffith Show, The Fugitive, The Twilight Zone and countless others, and in over 100 movies, including Splendor in the Grass, Norma Rae, Hang ‘Em High, and all four of the 1990s-era Batman films.

Pat Hingle is one of the most famous of former Saluda residents. He was the grandson of Mr. and Mrs. E.M. Patterson of Saluda, and he and his mother moved to town when his parents divorced. Pat’s grandfather was engineer on the helper engines up the Saluda Grade for 40 years. Pat’s acting career began at Saluda School, where he had a part in a school play. He went on to appear on Broadway in Cat on a Hot Tin Roof, on TV in Gunsmoke, The Andy Griffith Show, The Fugitive, The Twilight Zone and countless others, and in over 100 movies, including Splendor in the Grass, Norma Rae, Hang ‘Em High, and all four of the 1990s-era Batman films.

For Saluda’s Centennial celebration in 1981, Pat Hingle wrote a personal tribute:

“In the summertime of the early 1930′s, a bare-footed, tow-headed boy in short pants, no shirt, would stand on the main street of Saluda and wave at a man driving a huge locomotive steam engine. The man, with great dignity, would wave back. This would happen every time the engine came up the mountain pushing a train or backed down the mountain to wait for another one that needed to be pushed up. And every time it happened the boy would strut around like he owned the world or at least that corner of it.

The summer tourists probably thought the kid was nuts, but the town folk knew that the lad had just waved “hello” to his Grandfather and his Grandfather had waved back. And while they had already done the same thing four or five times earlier that day, it didn’t matter because they loved each other and the kid was a little nutty.

Later this same kid, now a teenager with a loud mouth that would serve him well in the profession he would take up, became a “caller” at the square dances. The ones on Saturday night at the high school gym with Lonzo Brookshire and his Smokey Mountain Boys, occasional vocal by John T. Coates. The ones for the young folks up at the Pavilion where Bingo for money was played on other nights. And the ones at Dr. Smith’s Childrens Hospital where there was the straight punch and at the other end of the porch there was the punch spiked with grain alcohol that would turn your ears around.

All this and the smell of honey-suckle, the early evening cry of the whip-poor-will, the call of a locomotive steam whistle from down in the hollow as it echoed across the mountain ridges, and names like Brinkus, Gurley, Ada, Burgie, G.L., and Robert Hugh.

All lovely memories a middle-aged man has of a little place called Saluda.”

“Hampered by deafness from the age of seventeen, I could not enter the ways of large endeavor.”

“Hampered by deafness from the age of seventeen, I could not enter the ways of large endeavor.”

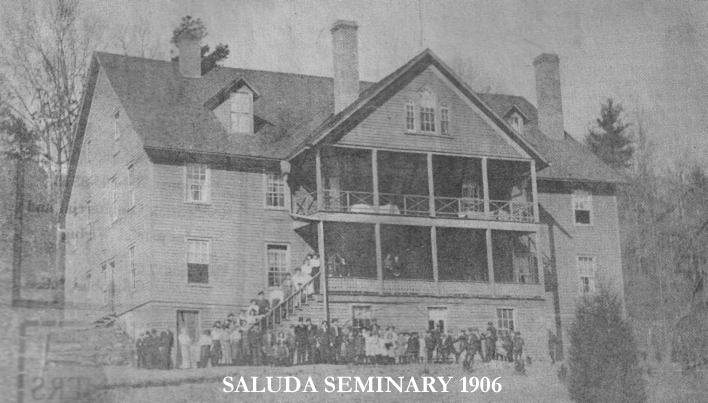

Emily C. Prudden (1832-1917) wrote those words in 1913, but they could not have been farther from the truth. Although also crippled by arthritis as an adult, she did indeed engage in large endeavors: Between the ages of 52 and 85, she founded seventeen schools in western North Carolina and upstate South Carolina. She made it her life’s work to educate white and African-American children across the region, bringing to them opportunities that they would not otherwise have had. Among the schools that Prudden founded were Oberlin Home and School- which later became Pfeiffer University- and Saluda Seminary.

Emily Prudden established Saluda Seminary in 1891 and wrote, “The large building at Saluda has been completed and rapidly filled with over 150 pupils…Prior to the erection of our seminary, the village had no school building, although there is still standing a house of logs without seats, window, door or chimney which formerly was used for a school.”

A brochure for Saluda Seminary in 1906 advertises instruction in writing, arithmetic, geography, health, physiology, history, composition, rhetoric, and music. The school was financed by selling used clothing and household items donated by supporters. Saluda graduate Brian Bollich became a Rhodes Scholar.

A brochure for Saluda Seminary in 1906 advertises instruction in writing, arithmetic, geography, health, physiology, history, composition, rhetoric, and music. The school was financed by selling used clothing and household items donated by supporters. Saluda graduate Brian Bollich became a Rhodes Scholar.

Click here for the little-known story of Miss Emily Prudden, who formed fifteen institutions in the Carolinas. Here is the link:

Playwright, director, and producer Keith Smith of Wind and Woods Productions is writing an outdoor drama about Emily Prudden and her work to be presented in 2013. It will be called The Legacy of Lick Mountain, and you can read a synopsis here.

Walter McQueen Stephenson was born in Saluda in 1911 and died in Shreveport, Louisiana July 4th, 1993. He was the son of Joseph Hoge Stephenson and Minnie May Guice Stephenson. Walter, nicknamed Tarzan, went on to fame by becoming a professional baseball player.

Walter McQueen Stephenson was born in Saluda in 1911 and died in Shreveport, Louisiana July 4th, 1993. He was the son of Joseph Hoge Stephenson and Minnie May Guice Stephenson. Walter, nicknamed Tarzan, went on to fame by becoming a professional baseball player.

His stats are below. Pretty good for a Saluda boy!

Bats: Right, Throws: Right

Height: 6’0”, Weight: 180 lbs.

Pros: Catcher

Born: March 27, 1911 in Saluda, NC

Debut: April 29, 1935

Final Game: September 30, 1937

Died: July 4, 1993 in Shreveport, LA

Major Leagues:

1935 – 1936 Chicago Cubs

1937 Philadelphia Phillies

Minor Leagues:

1932 Winston-Salem/High Point – Piedmont League

1934 Lafayette – Evangeline League

1936 Los Angeles – Pacific Coast League

1937 Montreal – International League

1938 Shreveport – Texas League

1939 Mt. Airy – Bi-State League

1939 Knoxville – Southern Association

1941 Shreveport, Oklahoma City – Texas League

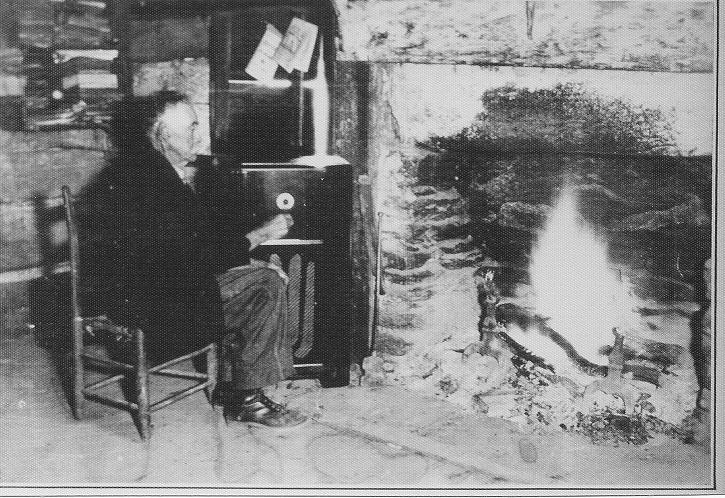

William Morris, known as “the Keeper of the Century-Old Fire”, was a descendant of Robert Morris, a signer of the Declaration of Independence. When his grandparents moved into a log house in Holbert’s Cove, they brought with them a live coal to start the hearth fire. Billy Morris became famous for keeping that fire burning as his parents and grandparents had, and it never went out in 150 years. He appeared on the “We the People” radio program in New York in 1936 and was presented with a battery radio for his cabin by the Philco Company.

William Morris, known as “the Keeper of the Century-Old Fire”, was a descendant of Robert Morris, a signer of the Declaration of Independence. When his grandparents moved into a log house in Holbert’s Cove, they brought with them a live coal to start the hearth fire. Billy Morris became famous for keeping that fire burning as his parents and grandparents had, and it never went out in 150 years. He appeared on the “We the People” radio program in New York in 1936 and was presented with a battery radio for his cabin by the Philco Company.

The fire went out a few years after Billy passed away at the age of 84. The last Morris relative in line to assume the fire-keeping duties fell ill and had to go into the hospital. The flame died during her absence.

-

-

Lola Ward grew up working in Thompson’s store, which had been started by her father. The store was “Information Central” for generations. Folks called the rotary phone to find out everything from the weight of new babies to the funeral arrangements of old timers. Miss Lola was the very heart of it all, stationed on her stool up front by the cash register well into her 90′s.

In the photo to the left, she is seen wearing her trademark apron smock and Bic pen on a ribbon. During the community-wide celebration of her 100th birthday in 2004, pens on ribbons were given away in her honor.

Lola passed away at the age of 103.

(Photos courtesy of Thompson’s Store.)

Charlie Ward was Lola’s son, and he and his brothers grew up working in the store just as their mother did. Charlie ran the store until he retired, leaving Saluda only once- to serve in the Korean War. He was best known for whistling in the market, hugging friends and strangers alike, and calling everyone “buddy”. Charlie was so appreciative of the townspeople for supporting his business that he decided to say “thank you” by holding a yearly barbeque.

Charlie Ward was Lola’s son, and he and his brothers grew up working in the store just as their mother did. Charlie ran the store until he retired, leaving Saluda only once- to serve in the Korean War. He was best known for whistling in the market, hugging friends and strangers alike, and calling everyone “buddy”. Charlie was so appreciative of the townspeople for supporting his business that he decided to say “thank you” by holding a yearly barbeque.

Charlie was often found working at Thompson’s Store’s signature butcher block. No telling how many thousands of pounds of sausage was mixed on it, nor ribeyes and chickens cut on it through the decades. It originated with the Baumberger family, and is believed to have come over from Switzerland with an ancestor in the meat profession in the late 1800s. (Watch for a shot of it in the video below).

Charlie summed up the feeling of Saluda when he once quipped, “If you’re in a hurry in Saluda, you’re in the wrong place”.

Having sold the store and retired, Charlie spent his last days relaxing and visiting with his grandchildren. He passed away in 2008. The annual Saluda Barbeque continues in his honor.

Here’s a visit with Charlie at the store:

Madame Phoebia Sullivan was a healer, herb doctor, mystic, prophet, and leader in Saluda’s black community. The story of her life and work is fascinating, and is well-summarized by Tom Haywood in the June 27, 1979 edition of the Thermal Belt News-Journal:

“She might have seemed a curiosity to some—this illiterate black woman from the Piedmont of South Carolina who carved fame and a considerable fortune from her adopted home in Saluda as a divine, faith healer, beholder of visions, and founder of her church.

“She might have seemed a curiosity to some—this illiterate black woman from the Piedmont of South Carolina who carved fame and a considerable fortune from her adopted home in Saluda as a divine, faith healer, beholder of visions, and founder of her church.

It was said she could heal by the touch of her hand while she gazed up to heaven and the thirty years in which she made her home on the mountain top her name spread through the nation and, perhaps, as no one before her or after in Saluda, was known to thousands in the world beyond the Blue Ridge where her faith had led her. For Madame Phoebia Cheek Sullivan was a woman of faith—with a deep abiding belief in what she professed.

Her story began in the backwaters of the rural South Carolina Piedmont—born to former slaves on May 15, 1864. She lived her first nine years much like any poor black child in Laurens County, South Carolina—close to the earth, without formal education, but raised in a culture rich with the religious fervor.

In her memoirs, “From The Cradle to The Crutch”, she records the first time her “power” became clear in a dream after she had celebrated her ninth “gingercake” birthday. That night she experienced her first vision. In it a man came to her riding in a chariot drawn by a snow white horse. Enchanted, she went with the stranger to the river where the horse and chariot rode over the waters. The dream continues, as Madame Sullivan recounted it in 1963 during her 99th year, with an oddly childlike quality, though steeped with Biblical symbolism. The girl tries to drink but small fish, symbols of Christ, appear to stop her and in the end she is given a Bible by the messenger who leaves her with the power to heal by the laying on of hands.

After she awoke, she claims to have retained the divine touch and allowed herself to become the instrument of the Lord, healing her neighbors in their afflictions with the support and encouragement of Doctor Wolfe, the local physician of Dials Township where she grew up. She continued her mission until she married at 19 and records she hid her “powers” from her husband “for fear of his thinking me strange”.

But her deception bore bitter fruit and she was stricken with the running sickness for ten years—a malady which made her race uncontrollably for hours-until another vision, her second, showed her ten herbs that grew in various trees and shrubs. Upon awaking, she gathered the leaves of the plants she had seen for her “cleansing tea” which cured not only her but others of their ills, including Dr. Wolfe who suffered from debilitating arthritis. The exact formula for her elixir is not known for whenever she made it she only allowed others to make the base and she personally added the “essence”.

But her deception bore bitter fruit and she was stricken with the running sickness for ten years—a malady which made her race uncontrollably for hours-until another vision, her second, showed her ten herbs that grew in various trees and shrubs. Upon awaking, she gathered the leaves of the plants she had seen for her “cleansing tea” which cured not only her but others of their ills, including Dr. Wolfe who suffered from debilitating arthritis. The exact formula for her elixir is not known for whenever she made it she only allowed others to make the base and she personally added the “essence”.

From there her life as a healer and divine was charted and took many forms before her death at 99 on December 15, 1963.

She came to Saluda two or three years after the death of her husband Henry Sullivan in the late 1920s with her large family of sixteen children and took refuge in a small wooden shanty near the site of the larger rambling structure she later built to house her brood and the twenty more she adopted over the years. After the first few years things improved for Madame Sullivan.

She came to Saluda two or three years after the death of her husband Henry Sullivan in the late 1920s with her large family of sixteen children and took refuge in a small wooden shanty near the site of the larger rambling structure she later built to house her brood and the twenty more she adopted over the years. After the first few years things improved for Madame Sullivan.

Slowly the word passed through the then sizable black community of her elixir and her healing abilities and the world began to literally beat a path to her door. There are still many in Saluda who remember the pilgrimage of countless blacks and many whites who made the stop on the train at Saluda for a jug of the brew. Of those who came few were disappointed.

Some came to drink her cleansing tea and others more seriously ill felt her touch. Her daughter Lula Sullivan who came to live with her in the early 1950s, remembers the numbers of the desperately sick who passed through her doors.

“I’ve seen them come in on stretchers,” she attests, “and walk out by themselves. Wherever she was in the house, they would lay them before her. And Mother would lay her hand upon Her proudest accomplishment, however, was the founding of the Sullivan Temple Missionary Baptist Church in 1947, a church in which her son James became an assistant pastor. But Madame Sullivan never preached in her church, for she didn’t give sermons as such. Instead, she quoted the Bible at length and those who knew her remember her scope in recitation as extraordinary. She could quote from the Bible verbatim for hours, though it’s unclear how she came by her knowledge since she couldn’t read and others had to handle her correspondence and read to her.

During the waning years of her life she remained robust and was a familiar sight walking down Greenville Street into town. “She looked like an angel with her snow white hair and the white apron she always wore.” remembered Lola Ward. “She was a beautiful woman.”

In her later years when the passenger trains ceased coming to the then faltering resort city, the pilgrims didn’t. Instead they came by bus, and on her birthday whole congregations from as far away as New York and Washington would charter them to come to Saluda to celebrate her birthday on the second Sunday in August. The vehicles would roll into town for days blocking streets during the huge multi-racial affairs as hundreds came to pay her homage”.

(You can read Phebia Sullivan’s Book of Dreams here.)

Robert Pace Born in Saluda in 1923, Robert Hugh Pace was the son of M.A. and Mintie Guice Pace. Until his death in 2010, Robert was the owner and proprietor of MA Pace General Store, a landmark Saluda institution that his father had founded in 1899. As columnist D.G Martin wrote, “He runs it much the same way his father did…The result is the opportunity for visitors to go back in time and experience a general store like the one where their grandparents traded.”

Robert Pace Born in Saluda in 1923, Robert Hugh Pace was the son of M.A. and Mintie Guice Pace. Until his death in 2010, Robert was the owner and proprietor of MA Pace General Store, a landmark Saluda institution that his father had founded in 1899. As columnist D.G Martin wrote, “He runs it much the same way his father did…The result is the opportunity for visitors to go back in time and experience a general store like the one where their grandparents traded.”

A graduate of Saluda High School and Wofford University, Robert was also co-owner of Saluda’s Western Auto. He served on many committees and boards and was instrumental in bringing First Citizen’s Bank and Autumn Care Nursing Home to town. He was also a very active member of his church.

Robert Pace is missed by everyone for many reasons, especially for his friendly smile and cheerful personality. He had a deep and extensive knowledge of Saluda’s history that he loved to share with anyone who would listen. A piece of Saluda was lost when Robert Hugh left us.

Ruby Hooper Ruby Thompson Hooper made history in 1984 as the first woman to run on a major party ticket for Governor of North Carolina, an office she sought again in 1992. After her ’84 primary opponent Jim Martin was elected, he appointed Hooper as liaison between the Governor’s Office and state employees in western North Carolina. She was later appointed deputy secretary of the NC Department of Human Resources.

Ruby Hooper Ruby Thompson Hooper made history in 1984 as the first woman to run on a major party ticket for Governor of North Carolina, an office she sought again in 1992. After her ’84 primary opponent Jim Martin was elected, he appointed Hooper as liaison between the Governor’s Office and state employees in western North Carolina. She was later appointed deputy secretary of the NC Department of Human Resources.

Born in Saluda in 1924 to Walter Lee Thompson and Lessie Mae Pace Thompson, Ruby graduated from Saluda School in 1941 as class president and salutorian. During her life she was chief nutritionist and dietician for Broughton Hospital, Western Carolina Center, and Grace Hospital in Morganton. She was often referred to as “Mother Hooper” for her nurturing and compassionate relationships with patients and fellow employees.

Over the years she served in various capacities in the American Cancer Society, the American Diabetes Association, the NC Council of Women’s Organizations, the NC League of Women Voters, the NC Committee on Fetal Alcohol Syndrome, the NC Caring Program for Children, the Governor’s Advisory Council on Aging, and many others. She received countless awards, including the Humanitarian Award from the Western North Carolina Chapter of Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Disorders Association, the 1990 Governor’s Community Service Award, and the 1991 award from the N.C. Community Action Association for distinguished service to the poor and disadvantaged. She was also named the “North Carolina State Mother of the Year” in 1993.

After over sixty years of public service, Ruby Hooper retired to Saluda with her husband John. She died in 2007 and is buried at Friendship Baptist Church.

James Leander “Daddy” Hart came to Saluda in 1881 after helping survey land around Saluda for Andrew Tanner. He built the original post office on Main Street and was responsible for building other Main Street stores. He was famous for his soft heart, and in his grocery business and undertaking business could never press anyone to pay their debts. He was also Postmaster for 17 years. Hart claimed that he “only went to school one day, and the teacher wasn’t there then”.

James Leander “Daddy” Hart came to Saluda in 1881 after helping survey land around Saluda for Andrew Tanner. He built the original post office on Main Street and was responsible for building other Main Street stores. He was famous for his soft heart, and in his grocery business and undertaking business could never press anyone to pay their debts. He was also Postmaster for 17 years. Hart claimed that he “only went to school one day, and the teacher wasn’t there then”.

-

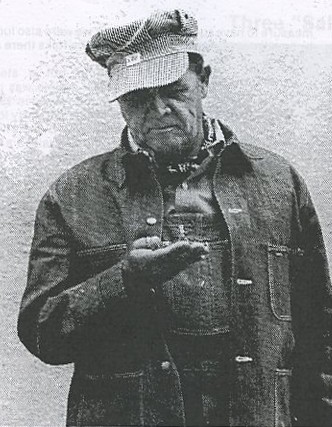

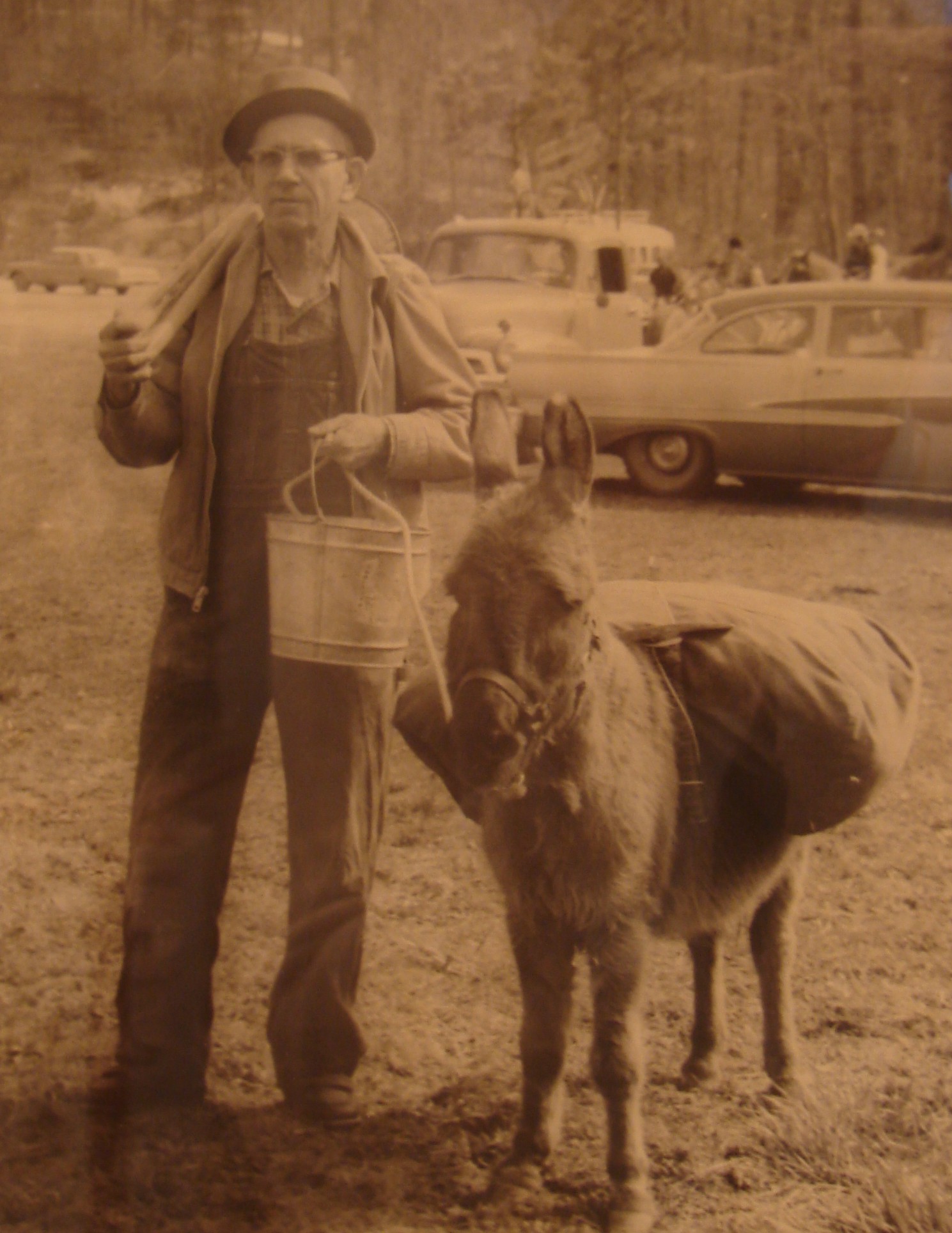

W.C. Ashley, “The Old Prospector” was a building supervisor for the Works Progress Administration during the 1930s and moved to Saluda from Columbus in 1941. After retiring from the building trade, he gave his full-time attention to his hobby of gem and rock “hounding”. Within a few miles of Saluda, he discovered a rare deposit of gem-quality onyx in all colors.

W.C. Ashley, “The Old Prospector” was a building supervisor for the Works Progress Administration during the 1930s and moved to Saluda from Columbus in 1941. After retiring from the building trade, he gave his full-time attention to his hobby of gem and rock “hounding”. Within a few miles of Saluda, he discovered a rare deposit of gem-quality onyx in all colors.

In the early 1960s, Saluda was in the doldrums. When an article in the Greenville News called attention to this fact, townspeople pitched in and remodeled the old drugstore building. Mr. Ashley then opened a rock and mineral museum, housing the largest collection of minerals and gems in North Carolina. The museum opened on March 24, 1962 and Ashley was honored by Saluda’s first-ever parade. Wanting to encourage expanded commerce in town, Ashley hung a sign in the museum stating that he would gladly vacate the premises if anyone wanted to set up a business in the building.

The collection is now under the care of grandson Eric Ashley and is no longer on public display, but Eric gives us a tour of the highlights here.

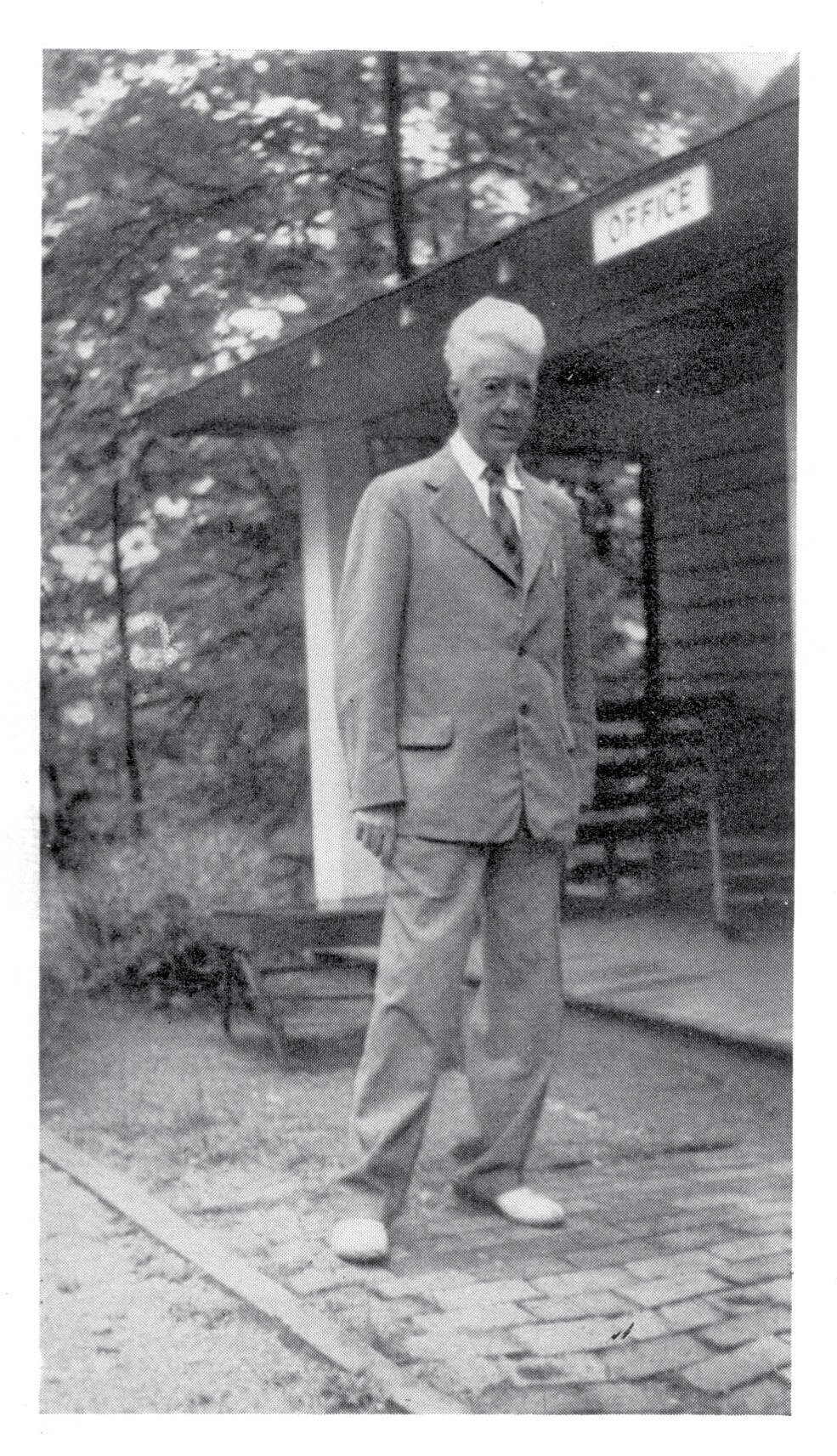

Dr. D. Lesesne Smith Dr. Smith was a pediatrician from Spartanburg who had a summer home in Saluda. In 1914 he decided to open a private Children’s Sanitarium on land near his home for the treatment of his year-round Spartanburg patients and any other sick children from the Lowlands who would benefit from a cooler and less humid environment. He converted “Bon Air”, the home which had been built for his second wife, into a hospital building and then bought up the surrounding land and buildings for accommodations for visitors and staff.

Dr. D. Lesesne Smith Dr. Smith was a pediatrician from Spartanburg who had a summer home in Saluda. In 1914 he decided to open a private Children’s Sanitarium on land near his home for the treatment of his year-round Spartanburg patients and any other sick children from the Lowlands who would benefit from a cooler and less humid environment. He converted “Bon Air”, the home which had been built for his second wife, into a hospital building and then bought up the surrounding land and buildings for accommodations for visitors and staff.

The success of the institution in improving the health of its young patients prompted a group of philanthropists to then establish the Spartanburg Baby Hospital in Saluda, a charity hospital to which Dr. Smith donated his services. When it became apparent that the care and climate in Saluda were cutting the infant mortality rate to a new minimum, pediatricians came from all over the South to study the hospital’s methods and conditions. The Southern Pediatric Seminar was founded in 1921, and for the next 38 years the first weeks of July saw Saluda filled to overflowing with pediatricians and their families, general practitioners, and representatives from drug firms.

Dr. Smith also developed nutritious feeding formulas for infants, including pablum. True to his altruistic nature, he refused to take any profit for these innovations.

Dr. Smith died in 1949, and the Seminar continued until 1958. The buildings that made up the Baby Hospital complex are now private residences, with the area still referred to as “Smith Hill”.

O.B. Garren: Otho Brownlow Garren was a master carpenter and built many of the historic homes in Saluda. He and his brother Jethro were also photographers, and thanks to their work we have many high-quality images of Saluda’s early days. Here is a short biographical slideshow about O.B Garren presented by his great-granddaughter Cindy Stephenson Tuttle:

Will Forrest was Saluda’s barber for nearly forty years. Raised on a farm near town, he opened a pool room and barber shop in 1913 in the Staton Building. He was one of Saluda’s most beloved citizens, evidenced by the number of folks who mentioned him during our oral history interviews.

Well-remembered for his sense of humor and skill at his craft, Forrest was also the source of endless fascination for many younger Saludans because of his wooden leg. In the accompanying photograph you can see its effect on his gait.

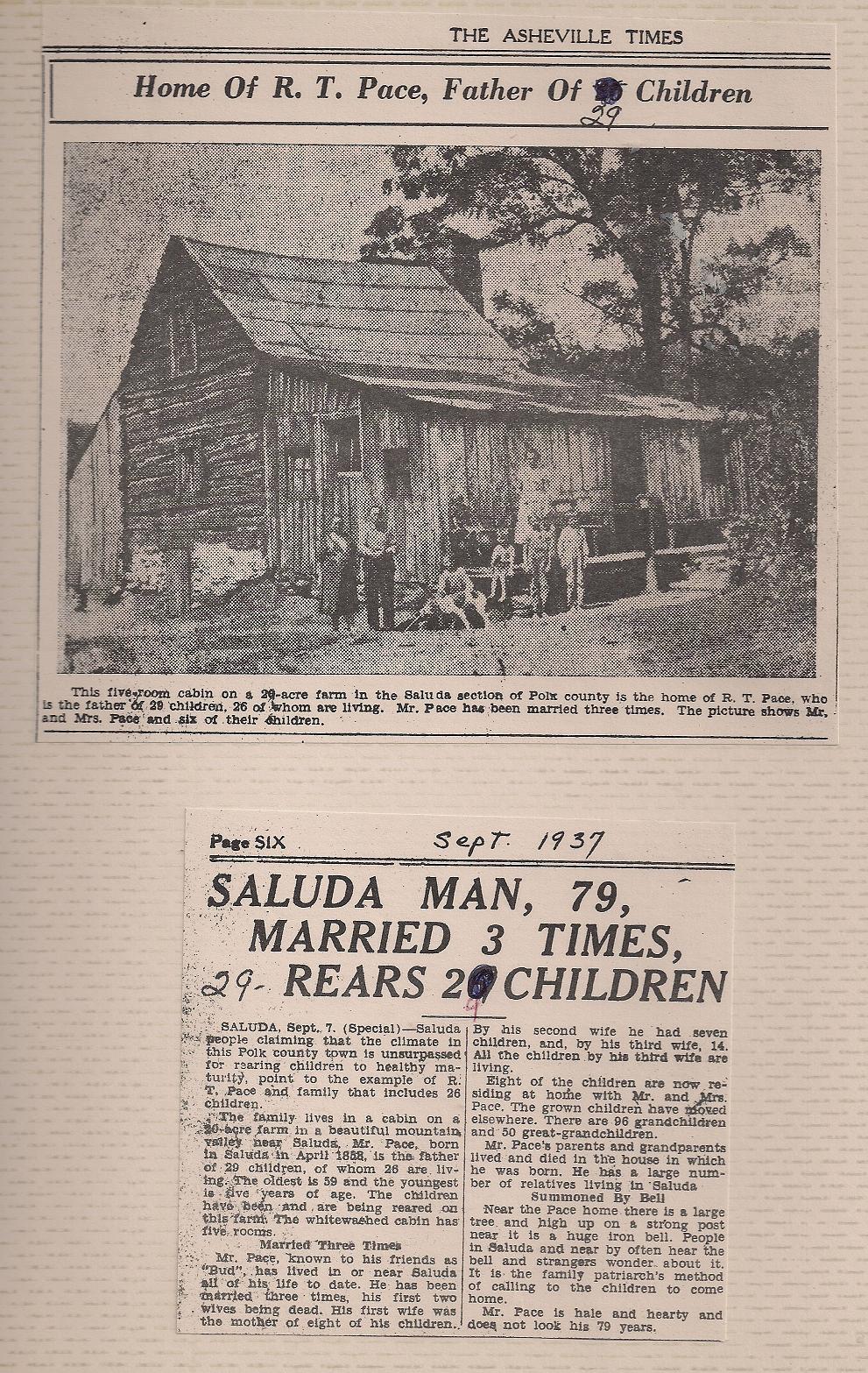

Ransom Taylor “Bud” Pace was a champion father. He raised 29 children with three wives, and the span between his youngest and oldest child was over sixty years! Many, many Saluda natives trace their lineage back to him. The Asheville Times covered the story in 1939: